3 Objection-Handling Lessons from Pandemic Politics

“How do you justify forcing small businesses to close while letting big-box stores stay open?”

“Lockdown measures aren’t working! Why should people follow your government’s advice?”

“Why are you putting teachers and students at risk by not mandating smaller class sizes?”

The pandemic thrust politicians into the spotlight like never before. As the surreal narrative raged on, every day elected officials from local Mayors and city councilors, to Presidents and Prime Ministers, took to the airwaves and social media. Their goal; to sell the public on their restriction and recovery strategies while promoting compliance with them.

In Toronto, where I live, the pandemic included nearly daily press conferences held by the Premier of our province, Doug Ford. Like any politician, Ford was constantly bombarded with questions, objections, and criticism. And yet, despite the onslaught, like others in his shoes, his response to the crisis actually boosted his popularity.

Indeed, during these media events, Ford consistently demonstrated critical and nuanced sales lessons in the way he responds to pointed questions. Here are three of the most powerful tactics from those objection-laden confrontations that you can incorporate into your sales motion:

1. Acknowledge and Empathize

Objections present opportunity for confrontation. This is certainly true when Salespeople hear things from their buyers like, “it’s too expensive” or “that will never work here!” But it’s doubly true when politicians field questions that are designed to intentionally provoke them. Ford and other master objection-handlers avoid these confrontations by using a tool known as a softening statement. As I discuss in Chapter 7 of my book, this non-confrontational way of introducing a response to an objection begins with acknowledging and empathizing with the objection.

For example…

Journalist: “How do you justify the crushing blow you’re dealing to so many small businesses by forcing them to close while letting big-box stores stay open? Isn’t that unfair?”

Ford: “Oh boy…my heart goes out to all of these small business owners! They pour their life savings into their business and work their backs off to make them successful. They’re the lifeblood of our economy and you’re right, it’s very unfair. In fact, this whole pandemic has been unfair to so many people and our amazing business owners are no exception.”

Whether Ford goes on to justify or defend his decision using other tactics (or avoid it completely as politicians do from time to time), the confrontational nature of the question has been disarmed.

This tactic works because when buyers launch objections, the amygdala, the part of the brain responsible for evoking strong emotional responses, goes on high alert, preparing for a defensive confrontation. A softening statement that both acknowledges the validity of the objection and empathizes with the audience acts as a calming mechanism. It lets the customer know that their concern is valid and legitimate, and it makes them more open to listening to you. It does not, however, endorse your agreement with the objection.

In a selling context, the tactic may sound like this:

Buyer: “I really like your product but it’s too expensive.”

Seller: “I completely understand. No one wants to spend more money than they have to on a solution like this.”

Buyer: “This isn’t a priority right now.”

Seller: “I totally get it. You have many things going on and need to give the most important things the most attention.”

2. Behavioral Labeling

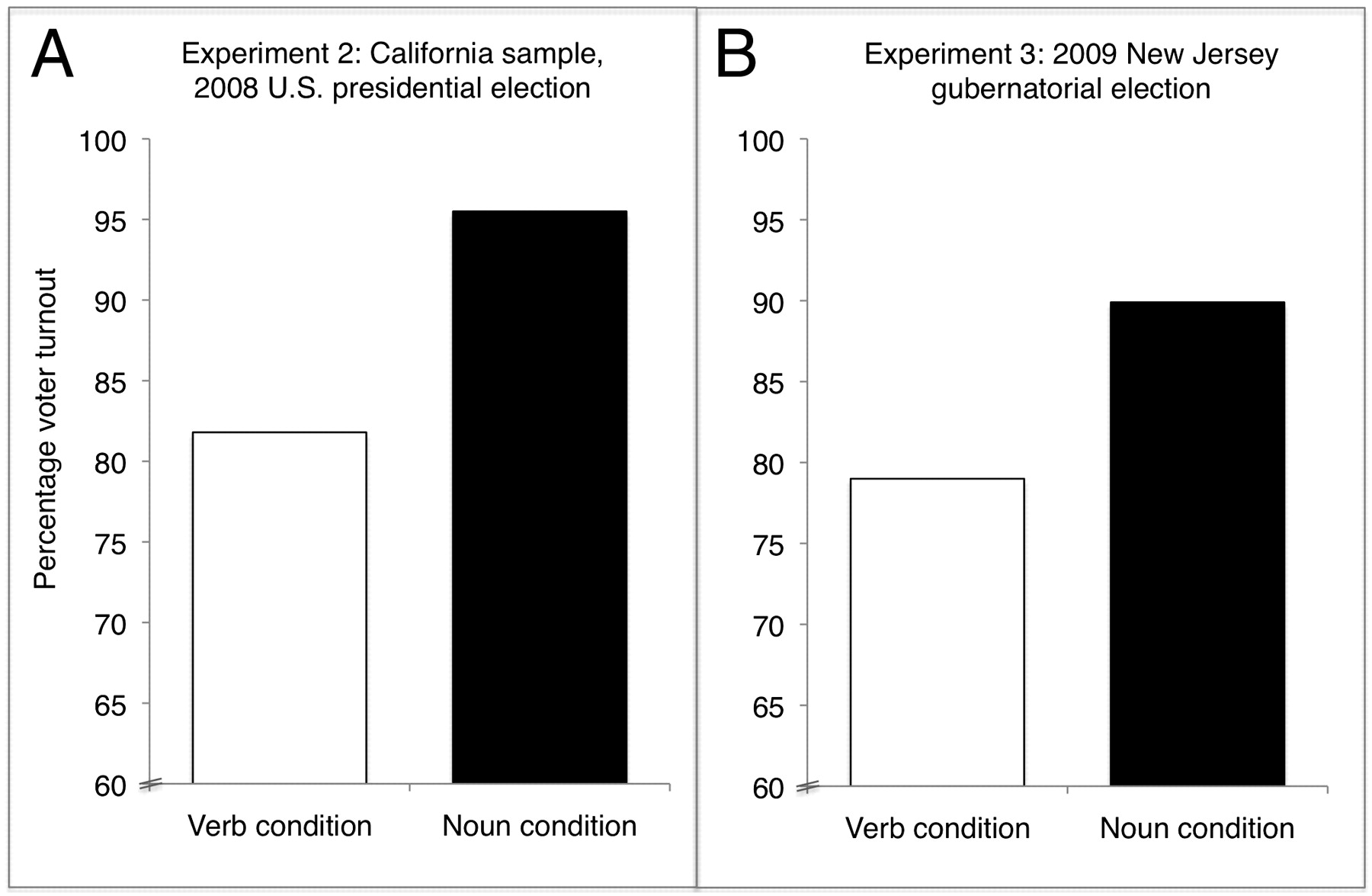

When it comes to influencing human behavior, the act of labeling has been scientifically proven to be a highly effective strategy. For example, in one study examining voter turnout, participants were asked a simple question with two different and randomized phrasings:

How important is it to you to be a voter in the upcoming election? (noun-phrasing)

How important is it to you to vote in the upcoming election? (verb-phrasing)

In both instances, labeling the individual as a voter (noun) versus simply as someone who votes (verb) was shown to result in increased voting behavior.

Source: Motivating voter turnout by invoking the self; Christopher J. Bryan, Gregory M. Walton, Todd Rogers, and Carol S. Dweck, PNAS August 2, 2011, 108 (31) 12653-12656

In this bestselling book, Atomic Habits, author James Clear cites a similar effect related to the creation of long-lasting behaviors. For example, identity-based mindsets such as thinking of yourself as a runner versus someone who runs or an author versus someone who writes, produces greater levels of behavior change.

Ford uses this same labeling tactic to handle pointed objections from the media while at the same time encouraging his constituents to model and comply with the desired behavior.

For example:

Journalist: “In recent days we’ve all seen stories of people ignoring social distancing rules by gathering in parks and having house parties. Are you concerned that the public will continue to ignore your rules?”

Ford: “I know Ontarians are good people who care about their families and the well-being of their neighbors. Sure, there are a few bad actors here and there, but the majority of our people follow the public health guidelines because they know deep down it’s the right thing to do.”

In a selling context, there are many ways this approach can be used. For example, labeling a customer as a “sophisticated buyer”, “experienced leader”, or “expecting world-class results” in your narrative can align their philosophy with yours.

For example:

Buyer: “We like your product but we’re just a small business and we’re not sure we need a solution as fancy as yours.”

Seller: “It’s true, we have a very robust solution and we’re not for every small business. But the reason customers like you choose us is because you have big growth plans. They know they’re not going to be small forever and they’re looking for a single solution that will satisfy their needs now and in the future. The thought of changing and disrupting their operation midway through is too painful for them.”

Note: in a recent article, I discuss a similar principle of using identity-based questions to drive buyer commitment.

3. Abdication of Authority

One of the most important aspects of dealing with objections in any negotiation is understanding how much authority each side has to grant commitments or concessions. For example, when you call your cell phone company to ask for a discount, the customer service agent may only be able to give you a small one. On the flip side, their manager likely has much more latitude in that area. Organizations often assign decision-making authority based on a hierarchy or team structure. But sometimes, even those at the top of that structure prefer to go into a negotiation with little authority or abdicate it to other people or entities.

A VP of Sales may have the authority to grant large price discounts. But to avoid getting pushed around in a negotiation with a particularly aggressive customer, they might choose to strategically (and temporarily) abdicate their authority to their CFO, saying something like, “unfortunately, a discount that large would need to be approved by our CFO but I’ve never seen her grant something like that before.” With the customer unable to speak to the CFO and the VP of Sales apparently lacking the authority to grant the discount, the hope is that the magnitude of the concession will be minimized.

Being the leader of the Province, Ford had the ability to set and overrule most of the pandemic rules under his government’s purview. But when he encountered a particularly contentious objection, he strategically abdicated his authority to other people and entities (typically not present for questioning) to avoid getting cornered.

For example:

Journalist: “Why do you continue to put teachers and students at risk by not mandating smaller class sizes?”

Ford: “I’ve always said that protecting the safety of our students and teachers is critical. But since I’m not a Doctor, when it comes to making decisions about class sizes or other medical decisions I always defer to our health command table* and our local medical officers of health.”

*Note: the make-up of this large health command table remained a mystery since the start of the pandemic. Ontario also has 34 different public health units, each with its own chief medical officer. This abdication of authority to a faceless entity makes it intentionally difficult for Ford to be cornered.

Lessons in modern selling can be found all around us! From how our children negotiate with us for sugary snacks and puppies, to simply asking someone out on a date. While the pandemic has presented its fair share of challenges, the sales insights provided by our politicians during this period of adversity can be an unlikely learning opportunity if we properly attune ourselves to them.

We promise never to send you junk or share your email! Just helpful sales insights.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!